Visit Saint Nectaire in Auvergne: the springs and caves

- Nature Source Chaude

- Published on

- Updated on 27 September 2025

Saint-Nectaire is located on a major fault line and is crossed by the River Courançon, known locally as the River Fredet. This allows mineral springs to rise to the surface.

This gives the small town in the Puy-de-Dôme department its surprising mineral wealth. The town stretches for around two kilometres from north to south through a narrow valley. No fewer than forty springs bubble up near the banks of the Courançon, sometimes even in its bed, not to mention the countless trickles of mineral water flowing throughout the town.

As a result, this sleepy town experienced a spa boom (1800–1914), with fierce competition between spa establishments rushing to exploit the springs once the necessary infrastructure was in place. There was also fierce competition between French spa resorts, some of which had multiple establishments: nine in Bagnères-de-Bigorre and Cauterets, seven in Vichy, six in Plombières, and three in Saint-Nectaire.

Having crossed the town from north to south, I invite you to discover the springs, thermal caves and closed or abandoned thermal baths that you can visit during your stay.

🧐 This will enable you to explore the town from top to bottom and learn more about its history and rich heritage.

Table of Contents:

Map of hot springs and mineral waters in Saint-Nectaire

The map shows the locations of most of the mineral springs. As the exact location of the hottest springs is unknown, their position is indicated relative to the buildings (former thermal baths) and caves in which they are located.

Further information about the springs (such as catchment, flow rate and temperature) can be found on the map and is taken from a 2003 report by the BRGM (French National Geological and Mining Survey).

The special characteristics of Saint-Nectaire waters

The mineral waters of Saint-Nectaire are distinguished by their unique composition and high mineral content (up to nine grams per litre), which varies according to temperature (between 8 and 53°C, except for borehole springs, which are even warmer). Some springs have a total mineral content that is among the highest in Auvergne. During the spa era, all of the springs’ water was drinkable, with some being used for bathing and showering.

The mineral waters of Saint-Nectaire have long been recognised for their high alkaline salt content and their particularly high concentration of bicarbonate ions. This is considered to be among the highest in the region. This was demonstrated by renowned chemists Messrs Boullay and Berthier, who analysed the waters in 1820.

On page 277 of the Journal de Pharmacie, Mr Boullay stated: “This appears to be the strongest alkaline water in France. It must be much more active and effective than similar waters, such as those from Mont-Dore and Vichy”.

In the Dictionnaire, also known as the Répertoire général des sciences médicales (General Directory of Medical Sciences), Dr Raige Delorme, a renowned 19th-century French doctor and medical dictionary author, stated: “Similar to the waters of Carlsbad, Mont-Dore and Vichy, the waters of Saint-Nectaire are used to treat the same morbid cases. The abundance of the alkaline principle, which is not found in such high concentrations in the latter, makes the waters of Saint-Nectaire even more effective in treating diseases for which this substance is most effective.’

Messrs Patissier and Bourtrand Charlard (19th-century pharmacists and chemists) stated: ‘The high concentration of baking soda in the waters of Saint-Nectaire is similar to that in the waters of Vichy. Like the latter, it makes urine alkaline and has a specific impact on kidney stones, bladder inflammation, chronic digestive disorders and liver and spleen issues.”

In the 19th century, the waters of Saint-Nectaire quickly gained a reputation for treating chronic rheumatism, gout, and other joint and muscle conditions in neighbouring regions. Depending on the length of stay, these symptoms could be alleviated considerably. Thanks to their mineral content, the waters were also an effective treatment for bone and joint diseases.

Source Pradinat

As you head towards the caves of Châteauneuf, you will find a slightly reddish puddle of water near a stream. These ferruginous mineral waters originate from a clearly visible stone catchment. They then flow into the stream, which is a tributary of the Courançon.

The spring provides cold mineral water (with an average temperature of around 14 °C) at a flow rate of 1.7 litres per minute, as measured in 1924.

Les Bains du Mont-Cornadore (former thermal baths)

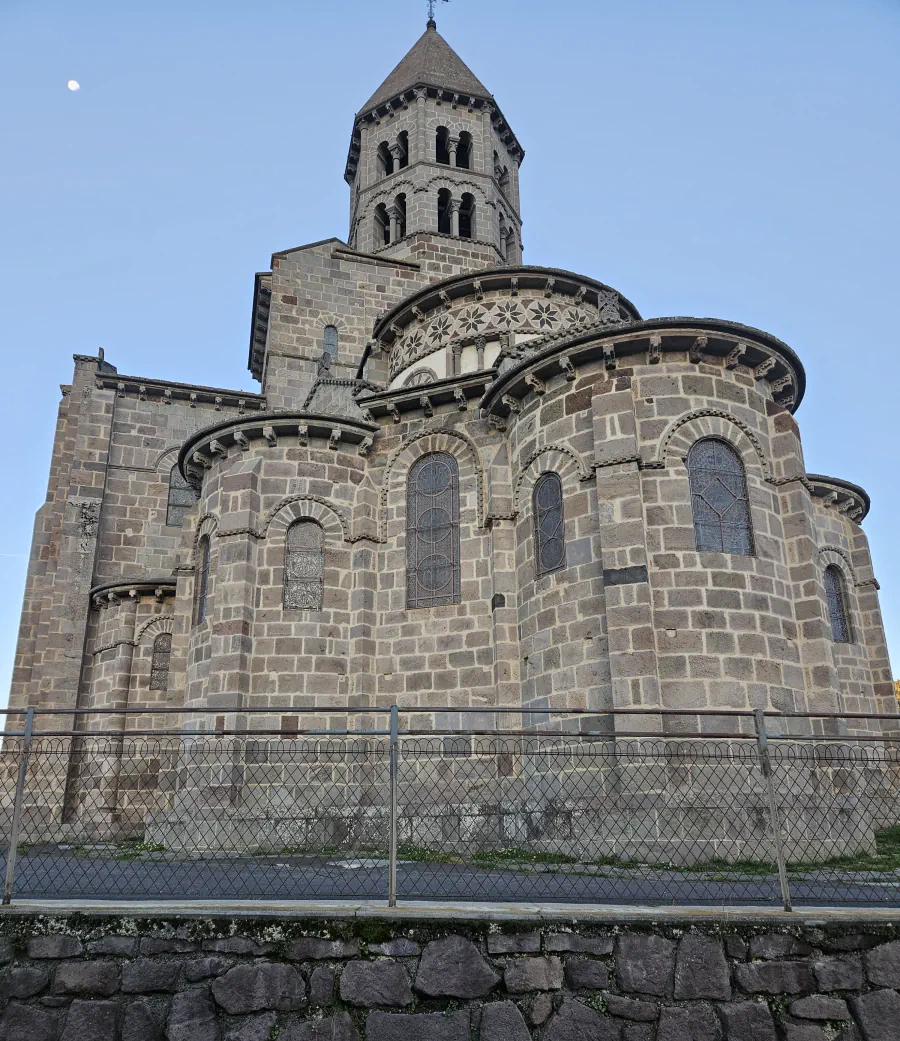

The hill of Mont-Cornadore, on which the upper town (Saint-Nectaire-le-Haut) and its old Romanesque church are situated, gave its name to the baths built to the west of it.

Mr Mandon became the owner of the spa establishment in 1865, after previously serving as its director. The street next to it is named after him. The spa building was constructed in 1832 by two partners, Mr Serre and Dr Vernière, five years after the discovery of the main spring: the Mont Cornadore spring.

As with any good spa, this one was built around the town’s most important thermal springs, which are notable for their flow rate above all else.

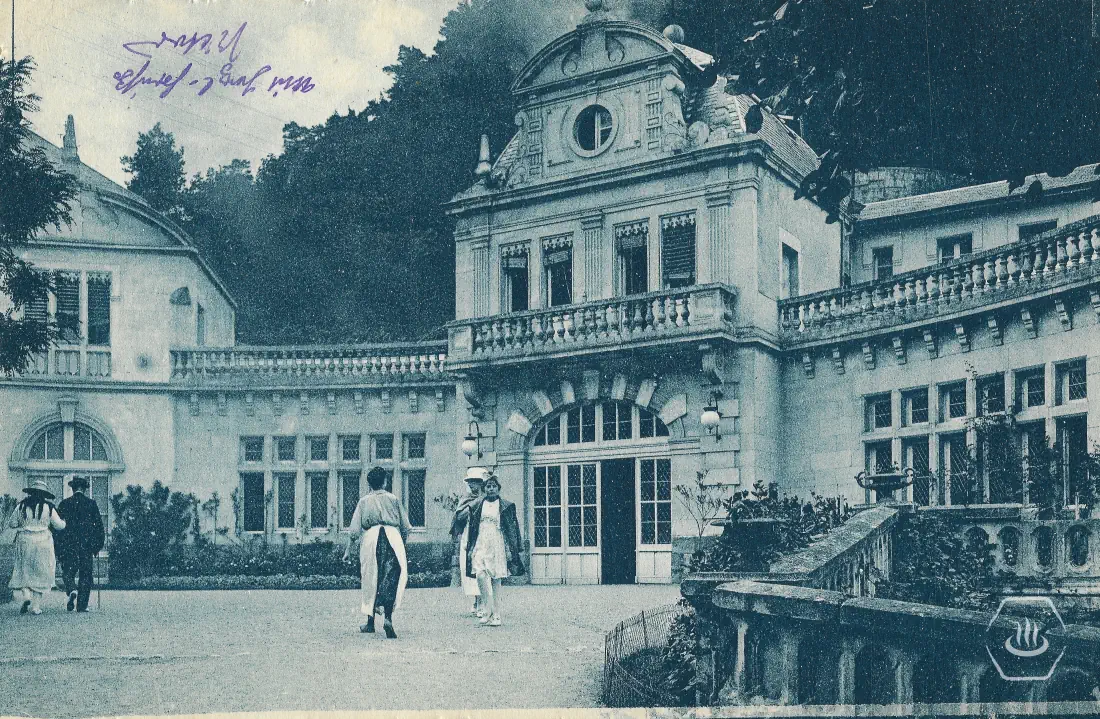

To the left is an old hotel built against a rock wall. The thermal baths are on the right. The two buildings are connected by a gallery, as can be seen in the postcard.

The thermal establishment dominates the area slightly, and the view from its upper floors includes the old Romanesque church, one of the region’s most beautiful historic monuments.

Originally, the upper part of the building was just a hotel annex comprising several rooms, while the spa facilities below evolved over time.

We are in the 19th century, at the dawn of the industrialisation of bathing. Technological advances, changing customs and capitalism profoundly affected spa rituals.

Like any good spa owner, Mr Mandon left no stone unturned. As early as 1865, he adapted to the requirements of the doctor-inspector and an increasingly affluent and demanding clientele. However, over time, the resort gradually became more of a holiday destination than a place to seek cures.

A variety of architectural styles (Neoclassical, Neo-Byzantine, Neo-Gothic, and so on) emerged at that time, giving rise to a veritable spa urbanism comprising thermal baths, hotels, casinos, kiosks, villas and more. In 1873, Mr Bruyère, the architect of Historic Monuments, built a triangular pediment with a large hall topped by a glass roof, providing access to additional cabins. This building has been listed as a Historic Monument since 2011.

♨️ Hot springs:

- The water that supplied the baths came exclusively from the Mont-Cornadore spring (with a native temperature of 39°C and a flow rate of 52 litres per minute) and was piped through lead pipe. It was also used for drinking cures in combination with the water from other cold mineral springs (the Parc spring, the Morange spring and the Romaine spring). The catchment of this spring, which is located beneath the spa establishment, is inaccessible. In 2003, the temperature of the spring was 30.4°C. This sulphurous spring gives off a smell of rotten eggs.

- Another spring, known as the ‘Source Intermittente‘ (Intermittent spring), was exploited from 1877 onwards. It had a temperature of 25°C and a flow rate of less than one litre per minute. Located beneath the spa building, this spring’s catchment area (a two-metre-deep well) was believed to have been covered and sealed, meaning any remaining water is now lost beneath the construction. This spring, which has now disappeared forever, used to supply a thermal refreshment bar. It was probably just a part of the poorly captured Mont-Cornadore spring.

- Finally, the spa establishment was supplied by the ‘Source du Rocher‘ (Rock Spring), which had a temperature of 25°C and an output of just 2.1 litres per minute. It was mainly used to supply the refreshment bar. The spring was discovered in 1875 during the construction of the hotel. The first application for an operating permit was submitted in 1895, followed by a second in 1928. However, both were rejected due to bacteriological pollution. It has probably since been filled in, as it is no longer visible.

The Cornadore Hotel is a building constructed above and behind the Grottes du Cornadore. In 1975, the section to the left of the red line in the picture was demolished and replaced by an embankment.

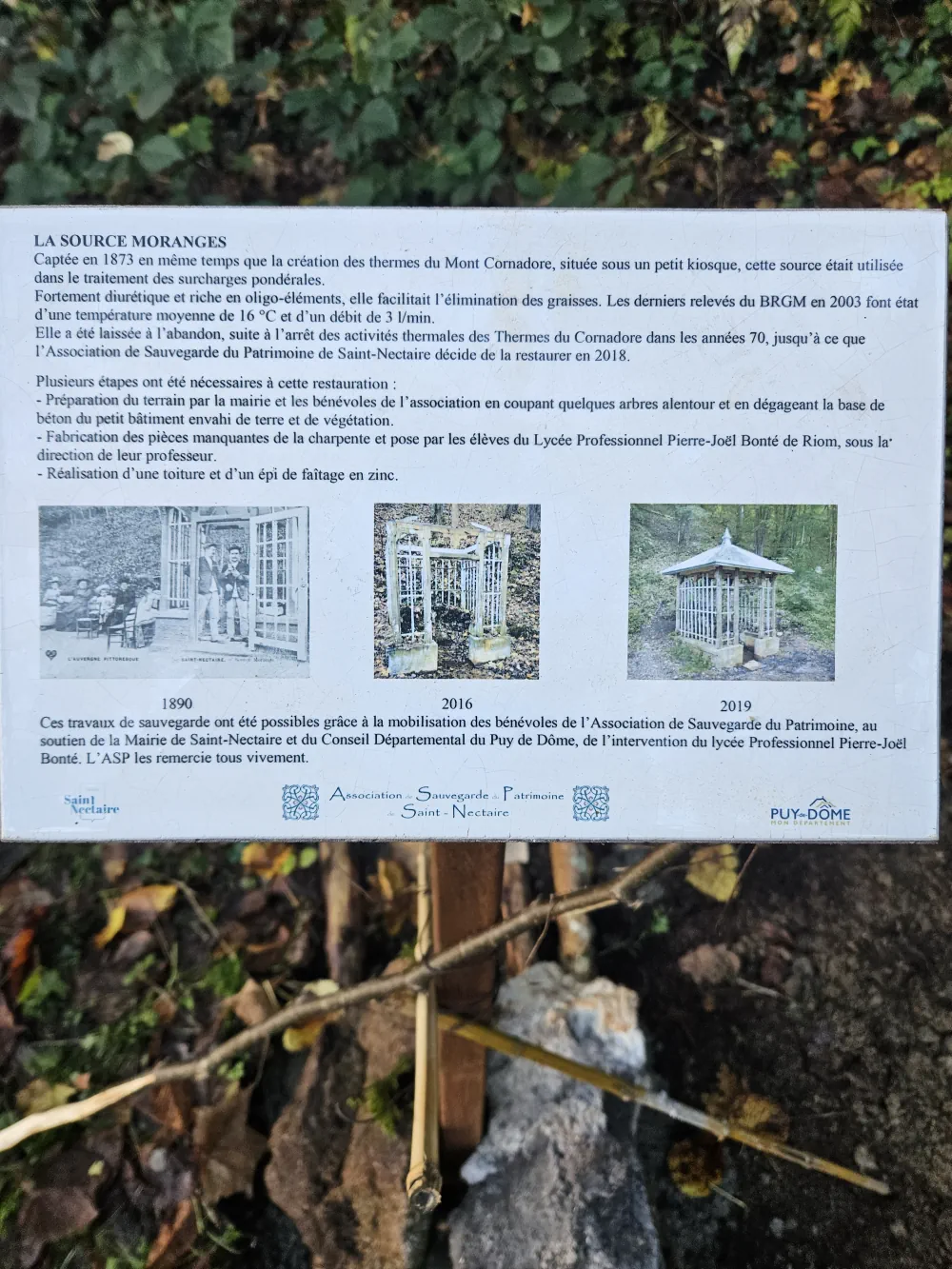

Source Morange

The spring is located approximately 450 metres from the Bains du Mont-Cornadore, on the outskirts of Saint-Nectaire-le-Haut, close to the road leading to Mont-Dore.

To reach the refreshment bar, you must cross the Courançon River via an old, single-arched stone bridge. Not far from there, a small zinc-roofed pavilion houses the spring’s catchment, which was installed in 1873.

During my visit, I noticed that an information panel had just been installed. This work was carried out by the Association for the Preservation of the Thermal Heritage of Saint-Nectaire. The panel revealed that the shelter used to be locked. A small fee was probably charged to bathers for any refreshments consumed on site.

🍵 At the time, people had to pay a considerable sum for each glass of mineral water served in a thermal refreshment bar — several dozen franc cents. It was rightly considered a genuine medicinal product that was rare and in high demand.

Visitors who wish to do so can now consume it free of charge.

With a total mineral content of 9 grams per litre, the water has one of the highest concentrations found in the Saint-Nectaire springs, giving it a slightly salty taste. It is also highly acidulated by carbon dioxide, which makes it very pleasant on the palate. Formerly used to aid digestion, relieve stomach bloating and combat obesity, these waters are now available to everyone. Finally, the water temperature was 15.6°C during my visit.

The springs of Les Grottes du Cornadore

Paid tour:

Find all the information you need on the official website: Les Grottes du Cornadore.

The path through the cave forms a small labyrinth that you can walk through for about 150 metres. At the start of the route, the ceiling is so low that developing the cave posed serious problems. The floor had to be excavated and, in some places, the ceiling raised to make the cave passable. If you are tall, keep your head down (helmets must be worn).

The gallery then descends into a fantastic mineral ballet, where sumptuous perspectives will captivate your gaze. On one side is a floor covered in coloured stalagmites tinted by iron oxides, which highlight the concretions.

Mineral water seeps down from the vault into small, irregularly shaped rimstone basins, also known as ‘gours’. The water is between 20 and 22°C, highly mineralised and has a concentration of between 8 and 12 g/l.

Another, larger rimstone basin can be seen from afar. This basin is located in a natural cavity that was discovered in the 19th century. Located in the middle of the room, the basin collects water from a petrifying spring with a temperature of 21.9°C. The basin is surrounded by white stalactites.

At the end of the descending underground gallery, you suddenly emerge into a room containing a rock shelter stretching several dozen metres. This place is also known for its unusual feature: a thick stalagmite which almost forms a column with the stalactites, from which mineral water drips.

These originate from two sources with similar compositions that contain sodium bicarbonate. However, the presence of certain mineralising elements means that they are completely different. You will learn about these elements during the tour, when you will also have the opportunity to sample the waters.

A small staircase leads up to a slightly elevated viewing area where you can admire the attraction.

This room is easy to explore, as the ground is level and there is natural lighting. A few metres further on, there is a kind of footbath filled with a few centimetres of mineral water. In places, there are some basins made of pisolite. In the past, this area contained more than fifteen bathtubs.

The wall is covered in living flora, which supports a variety of microorganisms. At the far end of the room is a vault adorned with short stalactites. Above this is an inaccessible room carved from granite that collects a thermal spring water at 22°C. This room once served as a tepidarium where visitors could acclimatise before moving between the caldarium and the tepidarium.

There is a door in the current room that leads to the caldarium, which is the hottest room. This large room has a relatively low ceiling. The walls and vaulted ceiling are almost bare.

These thermal baths were supplied with warm water (between 20 and 22 °C) via a network of wooden aqueducts.

There was no on-site water storage. The bathtubs did not have a continuous supply of water, which affected their physical and chemical properties. As I will explain later in the article, the baths were not taken in ‘running water‘.

In addition, the lukewarm water needed to be heated artificially. Volcanic stones, which had been heated to very high temperatures, were used to heat the water in the bathtubs to between 45 and 50 °C. This resulted in disturbances to the cave’s internal temperature and ambient humidity due to the sudden variations. The room temperature reached 60 °C, equivalent to that of a sauna.

The humidity of the walls, the carbon dioxide exhaled by the Roman soldiers (estimated to number around fifteen in the room) and the constant lighting provided by torches and animal fat lamps encouraged photosynthesis. This allowed algae, bacteria, cyanobacteria, amoebas and fungi to flourish, thereby disturbing the balance of indigenous microorganisms.

As the mineral water was artificially heated, some of its properties were lost. Therefore, when soaking, the Romans benefited more from the physical effects of the water (such as heat, buoyancy and water pressure) than from its lowered thermal properties.

However, the place resembled a military hospital where soldiers could receive spa treatments for wounds sustained in war. There was water in the bathtubs, as well as blood. Using mineral springs for drinking cures (where the virtues of thermal waters were fully expressed) was undoubtedly part of their routine, to complement the effects of bathing.

🏥Did you know?

During the First World War (1914–1918), wounded soldiers were taken to spa resorts where makeshift military hospitals had been set up.

Finally, you will find a petrification ladder in the room where calcium carbonate (and other minerals) are deposited on various objects by petrifying waters. The tour concludes at the shop, where you can purchase one of these crystallisations as a memento.

Source Giraudon

Once you have crossed the bridge opposite the entrance to the Mont Cornadore caves, walk up Rue Morange for a few dozen metres.

The spring’s water emerges from a tangle of vegetation on the left-hand side of the road. Its location is marked by a small sign that appears impossible to reach (see the drone photo). Brambles cover the area.

To capture the source and prevent any mixing with surface runoff, a 24-metre-long tunnel was dug into the ground. This tunnel dates back to the 1920s, but it is unclear how long it had been there prior to that. This highlights the lack of documentation regarding the exploitation of mineral springs, even in the relatively recent past.

Major work to improve the water catchment system began in 1920 and lasted eight years. Further recapture work was carried out in the 1970s due to a significant drop in flow caused by clogged hydromineral fissures. This transformed the 24-metre gallery into a much more complex structure.

The owner did not receive official authorisation to exploit the spring until 1973.

The spring’s water was piped to the newly opened Thermadore spa establishment in 1978 for use.

Exploitation of the spring was permanently suspended in 2003 due to frequent bacterial contamination (it had previously been temporarily suspended in 2001).

Source Edmond

In Saint-Nectaire, several springs — typically the coldest — were used in the petrification industry. Although this activity is still practised in Saint-Nectaire today, it was much more popular in previous centuries.

Buildings for producing inlay were constructed either on site or in close proximity to limestones springs or caves.

The Edmond spring, also known as the Pré Saint-Amand spring, has its waters emerge at the end of a gallery, which channels them to a building at the foot of the hill.

The esplanade around the Romanesque church and the surrounding area offer lovely vantage points from which to view the building and its private grounds. Inside, the petrification ladders are the most spectacular in Saint-Nectaire.

Mineral water enters the building at the top and flows down to the moulds on the lower floors. It is then drained through a hole in the right-hand corner of the wall. A 1924 survey found that the temperature of the emerging spring water was 32 °C, with a flow rate of around 66 litres per minute.

Source Gubler

At the corner of a residential building, behind a wall, hot water is escaping from a hole that appears to have been dug into the rock.

At first glance, this hole appears natural, but it was actually cemented from the inside and extended by several metres during work to develop a water catchment. The work (carried out in 1885, 1887, 1905 and 1936) was intended to increase the spring’s flow and protect it from infiltration by surface water. Originally, the spring consisted of three small neighbouring griffons on granite rock.

In 2003, the BRGM (the National Geological Survey) recorded a temperature of 30°C in the cave and its stagnant water. This confirmed that the spring had once been of significant interest. However, the licence to exploit the spring was rejected in 1936 due to bacterial contamination.

🦠Bacteriological contamination:

Any development work carried out near the springs or their source may result in the mineral water becoming contaminated.

However, waters from deep underground sources contains ‘indigenous’ microorganisms (such as bacteria, viruses ,archaea, etc.), which do not indicate external contamination. These microorganisms inhabit the deep biosphere, which is located kilometres underground.

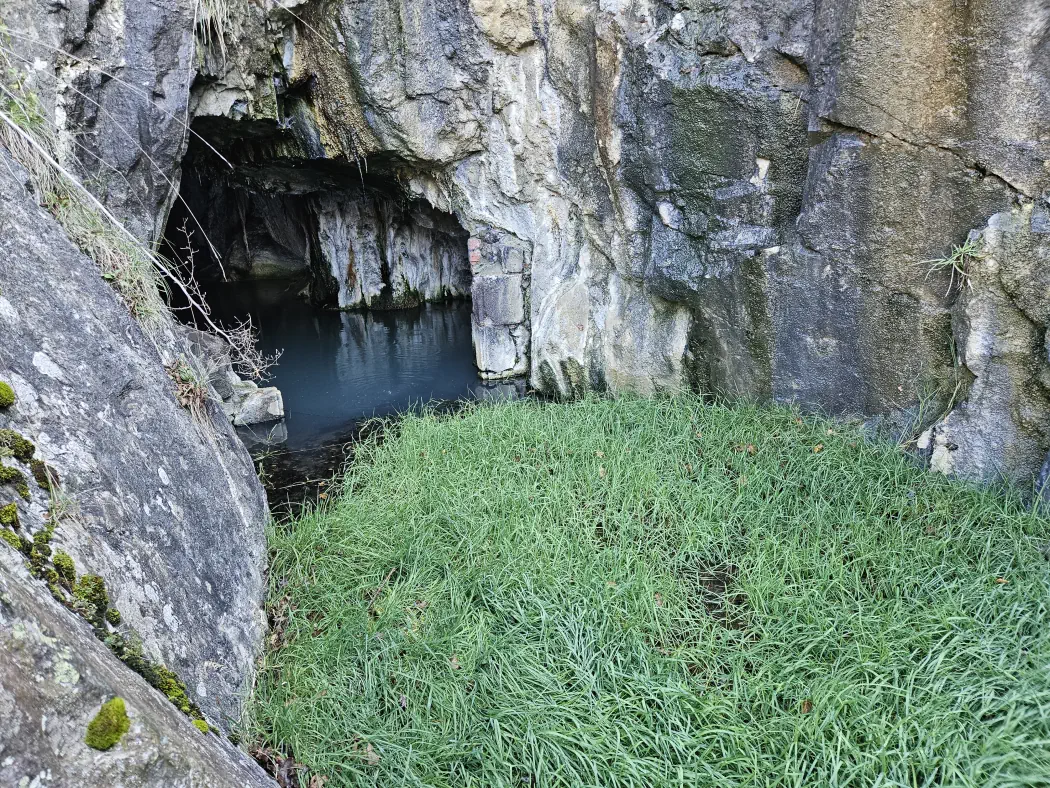

Source de la Voûte

The spring’s water flows naturally through the rocks that line the road opposite the post office in Saint-Nectaire.

To reach the cave (which is not visible from the road) that shelters it, you must first walk across grassy ground flooded by water from the spring. Boots are useless here, as you will sink up to your knees.

When you reach the spring, you will come to a cave dotted with concretions. The cave’s wide-open entrance reveals its beauty. These extraordinary combinations of mineral-rich water and rock like these are a real treat for the eyes.

Nevertheless, a large number of chronic skin and rheumatic diseases are also remitted by the high temperature of the water, which would be more difficult to achieve with lukewarm baths, even if the water is milky blue.

Taking a long bath at a comfortable temperature is essential to allow the body to absorb the chemicals dissolved in the water. For more information on the benefits of hot baths, read our article, ‘The amazing health benefits of a hot bath‘.

It is therefore regrettable that the spring does not reach a higher temperature; it is currently only around 20°C. Its low temperature and flow rate of 5 litres per minute have undoubtedly hindered its exploitation.

The salty marsh

In some areas of Saint-Nectaire, the soil is so saturated with salt deposited by water that maritime plants, typically found near the coast, flourish there.

This site is home to the richest marine flora in Auvergne. A panel at the edge of the Natura 2000 protected area provides information about these saltwater springs, which have created an extraordinary marine biotope of halophilic plants. The following species can be seen here:

- the sea plantain;

- the sea-milkwort;

- the saltmeadow Rush;

- the sea bulrush;

- the european barley;

- etc.

The springs of the Thermadore Centre, a former thermal complex

The Lignerat spa establishment was built in 1978 with the aim of reviving the region’s spa activities. However, it closed permanently in 2004.

When I visited in October 2024, the spa establishment had been completely demolished following the removal of asbestos. It was located to the left of the Aquatic Centre, a building constructed in 2002 that remains intact to this day.

Regarding the use of mineral springs as part of the drinking cure offered by the Lignerat thermal establishment, visitors had to go to:

- north of the town: the Parc spring and the Mont-Cornadore spring still supplied the refreshment bar of the former Bains du Mont-Cornadore establishment.

- south of the town: the Boëtte and Saint-Cézaire springs still supplied the the refreshment bar of the former Grands Thermes establishment.

The springs used for spa treatments (baths, showers, etc.) were sourced from boreholes drilled between 1981 and 1982. The thermal water from these springs was first mixed with water from the Giraudon spring in a vat to create the ‘Mélange Renouveau‘ (Renewal Mixture). The mixture was then stored in two 80 m³ tanks at 50 °C before being cooled using a plate heat exchanger to deliver water at 37 °C.

The management of thermal water resources had to be controlled.

💡About the mixing of thermal waters in Saint-Nectaire:

According to written records, the ancient thermal baths of Saint-Nectaire took great care in the 19th century not to mix waters of different temperatures from their springs, a precaution that was less common at other thermal baths at the time.

Consequently, each cabin (for bathing and showering) received water from a single spring, enabling the waters to retain their unique characteristics and thermal properties.

However, if the water from the spring was considered too hot for some patients, it was mixed with cooler mineral water from the surrounding area for showers.

Springs obtained from drilling:

Once the faults have been located, which is a complex geological task, drilling can begin.

The forage Charles (Charles borehole) is located 30 metres north of the thermal baths and reaches a depth of 57 metres.

In the past, the catchment was covered by a small wooden structure. The mixing vat was located beneath this shelter. With temperatures ranging between 50°C and 62°C, this spring, which originates from the borehole, is one of the hottest in the resort, alongside the Say borehole.

The forage Say (Say borehole) is located around 200 metres north-west of the thermal baths and reaches a depth of 100 metres. This borehole is connected to the Giraudon spring, meaning that the same water flows through two different pipes. The installation of the Say borehole reduced the flow rate of the Giraudon spring by over 30%.

The forage Sans Souci (‘Carefree borehole’), located around 300 metres south-west of the thermal baths, reaches a depth of 124 metres. It was named as such because the water does not cause limescale to build up on the installations and pipes connecting it to the thermal baths.

Although the total mineralisation of the Sans Souci spring is similar to that of the other two springs (Say and Charles) from boreholes, its composition differs.

When water from the Sans Souci borehole was in use, it was mixed with water from the Say borehole to prevent limescale deposits forming in the installation and connecting pipes leading to the thermal baths. However, as an additional precaution, a descaling agent was occasionally injected into the pipes.

There was once a time in Saint-Nectaire when visitors would gather in silent admiration before a geyser that spouted hot water high into the air with a loud roar. Even the most prosaic of people could not resist this spectacle.

In 1981, work on a borehole (the Charles borehole) searching for a hot spring caused an unexpected eruption of a giant geyser (the highest in continental Europe), halting work.

The sudden release of carbon dioxide, which was trapped in a groundwater layer beneath fractured granite, caused hot water to emerge at a temperature of 55°C. This geyser phase occurred in October–November 1981 and temporarily disrupted the flow of the Papon spring (see Les Fontaines Pétrifiantes).

Long before these three boreholes were drilled, the Saint-Nectaire thermal aquifer had already been the site of drilling operations aimed at discovering new mineral springs. One of these was a 12-metre well discovered before the First World War, and the other was a 31-metre well discovered in 1928. Both were named after the Antonia spring and were sheltered under a hut (located in the photo above). This structure has since disappeared.

Source du Scay

Just behind the Thermadore Centre, there is a metal bridge that crosses the Courançon River. This bridge provides access to the spring. Inside the building, you will see a petrifying fountain with a ladder inside it. Water at 30°C flows from a drainage channel at the base of the building.

The spring is captured to the north-west of the building. There are two covered basins, which are protected by a grille. According to BRGM records, the spring’s flow rate reached 32 litres per minute in 2003.

The springs of Les Fontaines Pétrifiantes

Paid tour

Find all the information you need to visit the site on the official website: Les Fontaines pétrifiantes.

🗺️ In one of the rooms, you will come across an attractive world map of hot springs.

The tour begins with a recorded documentary shown in a room on the first floor of a fairly modern building, which was renovated in 2003.

This room opens onto a sloping gallery, where visitors can take their time reading the informative panels. The cemented path is easy to walk on and takes visitors from start to finish. The underground route is straightforward.

Here, you will discover a small, curled-up cave. The path is clear, with the first concretions appearing on the left in the form of flowstones, fistulous formations and stalactites.

On the right wall, just before a low wall (hot spring), there is a recess adorned with concretions.

A petrifying spring trickles down from the vaulted ceiling onto surfaces wrinkled with micro-gours and beautiful, bird-shaped incrustations, heightening visitors’ aesthetic emotions.

Beyond this corridor, a low wall holds back water from a hot spring, which adds a pleasant touch to the walk.

But where does this water come from? It originates from two captured sources where the waters converge in an underground gallery situated ten metres beneath the pool.

This gallery is fed by the Papon hot spring (52°C) and a cold mineral spring (18°C), which helps moderate the excess heat.

Depending on the flow rate of each spring, the pool’s temperature averages at 35°C. During my visit, my thermometer read 37°C.

♨️ The Papon spring:

The Papon spring actually consists of several underground springs (at least five), which were discovered and named in the 1910s. The springs probably communicate with each other, meaning the same water (from the same deposit) feeds the five separate conduits, each of which has a different name.

However, all these waters flow into an underground gallery, where they mix with cooler mineral water at 18°C. These springs are all rich in sodium and bicarbonate, with a mineral content of around six grams per litre.

The tour takes in several rooms (including spaces for documentary screenings, exhibitions, and workshops), which makes the visit more interesting. Before the shop is a final room that provides access to a platform. From here, visitors can see various objects displayed on a 14-metre-high petrification ladder that are out of reach.

Sources Léon et Eulalie

The Léon spring is located on the left-hand side of the road to Sapchat, near the Hôtel du Parc. To reach it, you have to climb a steep slope towards the edge of the woods. Therefore, the 50-metre-long gallery is not visible from the road.

Once you are there, the area is so overgrown with brambles that it is impossible to stray from the path.

Another spring is the Eulalie spring, which is located around 40 metres away in a parallel gallery. I was unable to find it myself. In 1924, the temperatures of these two springs were 28 °C and 30 °C, respectively. Today, however, the temperature of the Léon spring is only 16–17 °C.

These two springs were therefore primarily used as the raw material for petrification. They are still channelled to a small establishment located a little further down the Route de Sapchat (Sapchat road).

Sources Bélonie

The three Bélonie springs (Sainte-Marie, André and Bauger) are located close to each other at the foot of the partially volcanic Puy d’Eraigne granite mountain. The springs are situated in an abandoned garden next to the Hôtel de l’Ermitage, bordered by the Route de Sapchat.

In the past, visitors could sample the water supplied via a simple drinking fountain. It was renowned for its pleasant taste.

The ministerial authorisation to exploit the springs was revoked in 1958 due to several years of neglect. These cold, sodium bicarbonate springs contain iron and have a temperature ranging between 12°C and 14°C. Their composition is very similar to that of the Rouge spring.

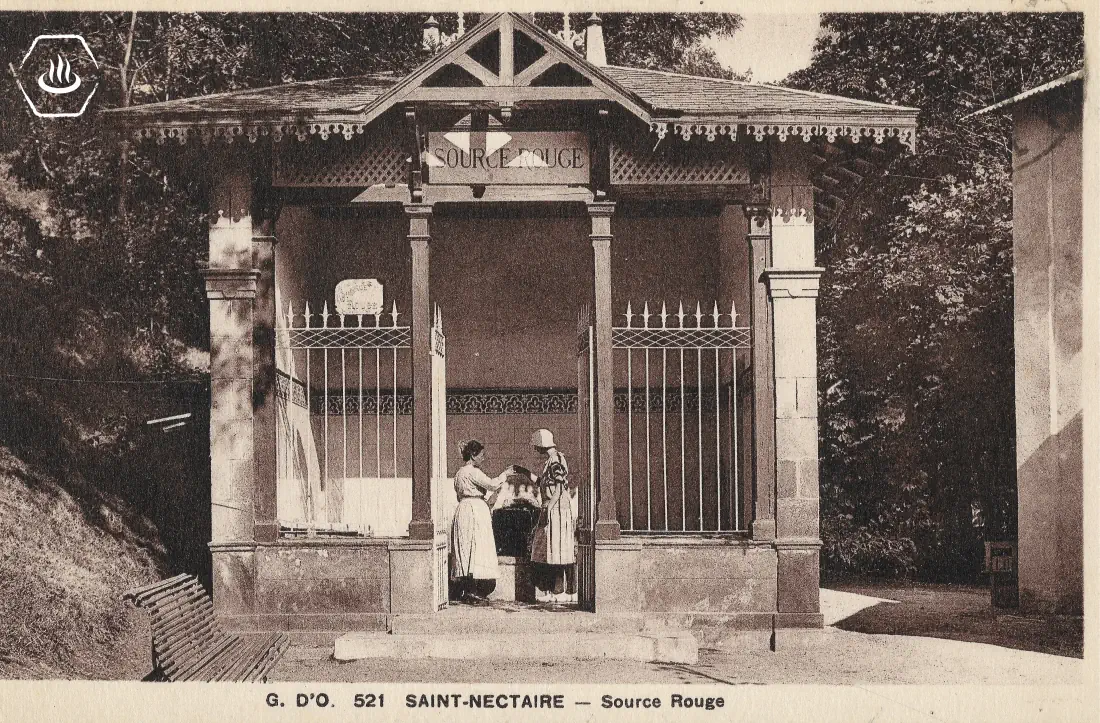

Source Rouge

The Source Rouge (Red spring) gets its name from the red deposits left behind by the water. It springs up at the edge of the Route de Sapchat, near the Puy d’Eraigne, probably only a few metres from the Bélonie springs. The catchment area could not be found.

In 1895, a 5-metre-deep well was drilled through the granite in order to access the spring (it is not known exactly when the spring was first accessed). A 30-metre pipe connects the spring to a refreshment bar. This is located in an elegant pavilion in the corner formed by the roads to Sapchat and Saint-Nectaire-le-Haut.

Mr Versepuy, the owner of Rouge Spring, was Mr Mandon’s son-in-law. He also owned the Cornadore Hotel and took over the thermal baths of the same name around 1870. As with the Morange refreshment bar, this bar was reserved for his guests.

Access was protected by a sturdy iron fence. It seems that a small fee was required to enter, as was the case with the Morange spring.

It is said that all kinds of trafficking took place there. The main form of trafficking involved attaching a cup to a long stick in order to draw water from the spring. It is said that some sick people would drink several days’ worth of water in one go.

💡Drinking cure:

Since the end of the Second Empire (around 1870), people have used graduated glasses for drinking water. These were invented by Dr Casimir Daumas of Vichy. At that time, mineral water was considered a medicinal product and sold at a high price, so it was consumed in small quantities. This inevitably reduced the effectiveness of the treatment.

Apparently, this water, which was 23 degrees, was very pleasant to drink. However, when the refreshment bar closed down definitively, it was replaced by the Coquille spring, which tasted less pleasant.

Like all Saint-Nectaire springs, this is a sodium bicarbonate spring. It is salty and fizzy, and its red colour indicates a high iron content. Its flow rate was 22 litres per minute.

Les Bains Boëtte – Grands Thermes (former thermal baths)

The Grands Thermes establishment is located at the junction leading to Saint-Nectaire-le-Haut, directly opposite the Red Spring Pavilion.

After discovering several springs (the Rocher, Boëtte and Cézaire springs) in 1822, Mr Boëtte decided to build a spa establishment there.

In 1824, he blocked off access to the springs and had a small square building constructed, which was named after him until 1890: Les Bains Boëtte (Boëtte Baths). Water from two springs was piped upstairs to tanks. The ground floor contained nine rooms (mostly showers and two concrete bathtubs), arranged around a square hall, and it was here that the water was distributed.

In 1888, Mr Giraudon — an entrepreneur who already owned the Bains Romains — acquired the disused Bains Boëtte. He had grand plans for the site and built the Grands Thermes in a neo-Renaissance style, giving the building a semi-circular shape.

In 1993, the building was renovated and became the tourist office.

The nearby Boëtte and Saint-Cézaire springs were captured in a gallery beneath the building. This gallery connects to the banks of the Courançon River. The high carbon dioxide content of the Boëtte spring creates significant pressure, pushing some of the water up into a vaulted room on the ground floor.

When I entered the room next to the tourist office reception desk, I immediately noticed the strong smell of rotten eggs. You will need to ask reception for the key. Several compartments had been carved into the rock itself and the side walls were covered in cement. There was also a trickle of water running down the granite. I took a few photos and then left.

This smell is great for your lungs. Read our article, ‘How to Cleanse your lungs with simple, natural ways‘, to find out more.

💡Spring capture:

As they flow into the basement of the building, the sulphurous waters leave limestone deposits, forming travertine around the two sources.

The catchments become clogged with coloured carbonates, to the extent that one of them — the Boëtte catchment — has disappeared entirely. Without regular maintenance, such as cleaning and descaling, the flow and temperature of the springs can be reduced by the limestone deposits, thereby impacting their therapeutic properties.

→ The Saint-Cézaire spring, formerly known as the ‘Petite Source Boëtte’ (little Boëtte spring), had an original temperature of 44°C (to be verified). Currently, no temperature data is available. Its waters flow approximately five metres east of the Boëtte spring.

→ The Boëtte spring, formerly known as the ‘Grande Source Boëtte’ (Great Boëtte Spring), is the most abundant. It originally had a temperature of 40°C. The first catchment was developed between 1823 and 1824. However, the spring’s flow gradually weakened until it could no longer be exploited. Its flow rate fell from 36 litres per minute in 1843 to just three litres per minute by 1885. Each time there was a drop in flow, the spring was recaptured (in 1880, 1885 and 1921). Since the last recapture in 1921, however, very little information has been recorded. It appears that the spring’s temperature is now around 30°C, with a flow rate of no more than 20 litres per minute.

🫗 Thermal refreshment bar (or rotunda):

Lead pipes were used to transport water from the two springs to the storage tanks for the baths and the drinking fountains located under the dome on the square in front of the tourist office.

Each lead pipe is only 30 to 40 metres long, from the source to the refreshment bar. This short distance probably has little impact on water quality. However, using lead pipes to carry medicinal water, as at the Bains du Mont-Cornadore, may pose a risk of contamination.

Water absorbs lead from lead pipes (☠️ which are toxic). The hotter and more acidic the water is, and the longer it remains in contact with the pipes, the more lead it will absorb.

By the time they reached the refreshment bar (and the baths), the water from the Cézaire and Boëtte springs would undoubtedly have deteriorated in quality compared to its original state.

Although they have been banned since 1995, lead pipes were widely used in the 19th and 20th centuries. According to a 2013 report by the General Inspectorate for the Environment and Sustainable Development (IGEDD), they are still present in around 7.5 million French households. Further information on the toxic effects of lead on health can be found on the Ministry’s website: https://sante.gouv.fr/sante-et-environnement/batiments/article/effets-du-plomb-sur-la-sante

🛠 Pipes:

Lead pipes, which cause lead poisoning, iron pipes that are susceptible to corrosion, cement pipes mixed with carcinogenic asbestos, plastic pipes (see study), etc., all have disadvantages.

Sulphurous water can react with certain reagents, such as lead. This can result in brown staining inside the pipe and the formation of sulphur crystals.

In 2003, the water temperatures at the Saint-Cézaire, Boëtte and Mont-Cornadore fountains were 31.6 °C, 33.5 °C and 30.4 °C, respectively. This was the last time they were used for drinking cures by guests of the Thermadore spa.

The significant difference in temperature compared to the native temperature of the springs suggests that the water distributed at the drinking fountain had different properties, in addition to those introduced by lead piping. Furthermore, the flow rate at each drinking fountain (those in Saint-Cézaire, Boëtte and Mont-Cornadore) decreased by at least half between 1930 and 1987.

💡Around the springs:

‘Armed with their prescriptions, water drinkers waste no time in making their way to the indicated springs. They pay little attention to the sometimes turbulent history of these waters, and even less to the regular scientific analyses carried out to check their composition and purity. They become familiar with the names of the springs alone.’ (Quote from the book: La vie quotidienne dans les villes d’eaux (1850–1914) by Armand Wallon).

💡Social security coverage for thermal spa treatments:

Thermalism was not recognised as a distinct form of therapy until after the Second World War. Social security was not established until 1945, and decrees relating to crenotherapy (thermal medicine) were not passed until 1947. Thermal cures were then covered by social security. Consequently, most of the resorts’ clients were people covered by social security.

Bains Romains (former thermal baths)

The discovery of one of the main springs (used for bathing) in Saint-Nectaire-le-Bas dates back to ancient times. Remains left by the Romans have been found.

In 1812, Mr Mandon, a Saint-Nectaire resident, discovered the Gros-Bouillon spring (also known as the Mandon spring) while digging a cellar. He then collaborated with Dr Marcon to build baths comprising two pools to make use of the Gros-Bouillon spring, as well as two others: the Vieille Source and the Fontaine de la Vieille-Voûte. The latter two springs were already in place as a thermal fountains, but their exact origin is unknown.

However, in 1817, the architect M. Ledru wrote to the prefect to inform him of the squalid conditions in which the springs were being exploited. Moreover, at the beginning of the 19th century, thermalism needed to reinvent itself. Ledru described the building as horrible and dark, and criticised the poor-quality equipment used for exploiting the hot springs.

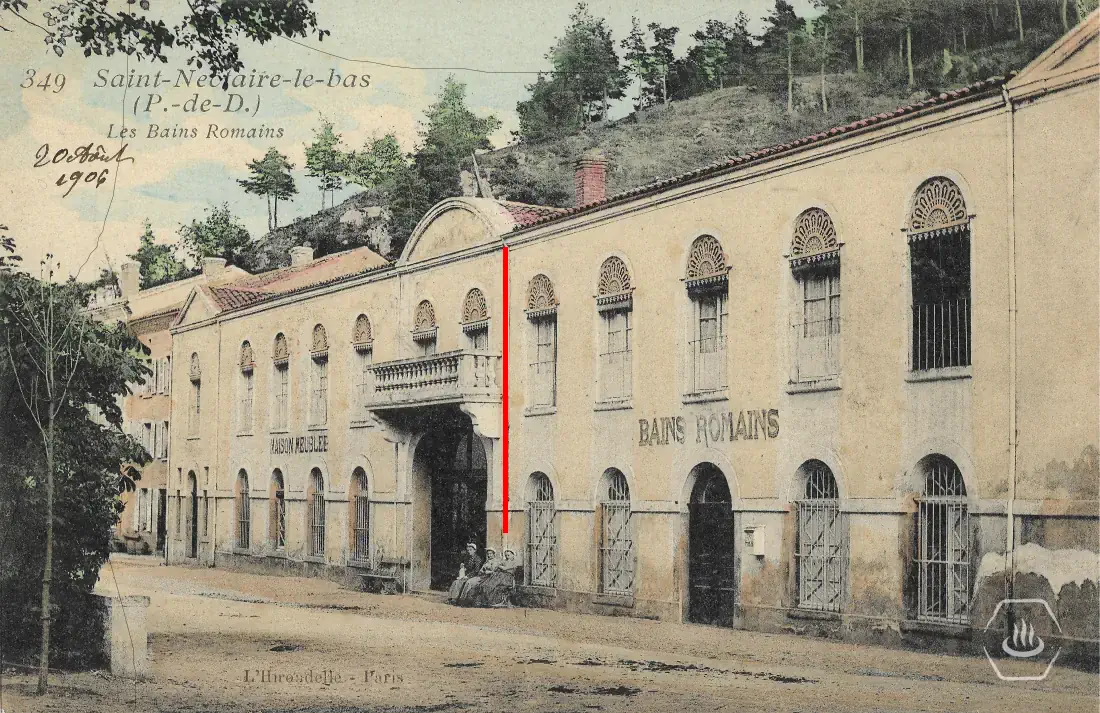

Consequently, Mr Mandon decided to rebuild a larger establishment on the springs and named it Les Bains Romains. This was inspired by the ancient Roman baths that had been unearthed during the construction. In the image below, Les Bains Romains can be seen on the right-hand side of the building. The left-hand side corresponds to the hotel (‘Maison meublée’, or Furnished house), which was probably built around 1840.

The main building comprised ten rooms, several showers and twelve concrete bathtubs, all arranged around a large, well-lit, vaulted hall. One of the main advantages of the baths was that they were taken ‘in running water’ (as it is called in French) and at a natural temperature.

🛁Bain en eau courante (bath in running water):

A ‘running water bath’ circulates thermal water continuously inside the bathtub, just like in a natural thermal bath. This ensures constant water renewal and consistent temperature. This optimises the transcutaneous penetration of the minerals and organic substances dissolved in the water.

The waters of Saint-Nectaire, which originate from the main springs (used for soaking in the three ancient thermal baths), had undeniable advantages. They could be administered at their natural temperature as soon as they bubbled up from the rock. This avoided the excessive stagnation that promotes degassing and the flocculation of mineral substances. This would otherwise result in a rapid loss of medicinal properties.

This involved administering ‘running water baths’, where a slight loss of water was compensated for by continuously flowing water, which maintained a constant temperature of around 36°C. I will come back to this later.

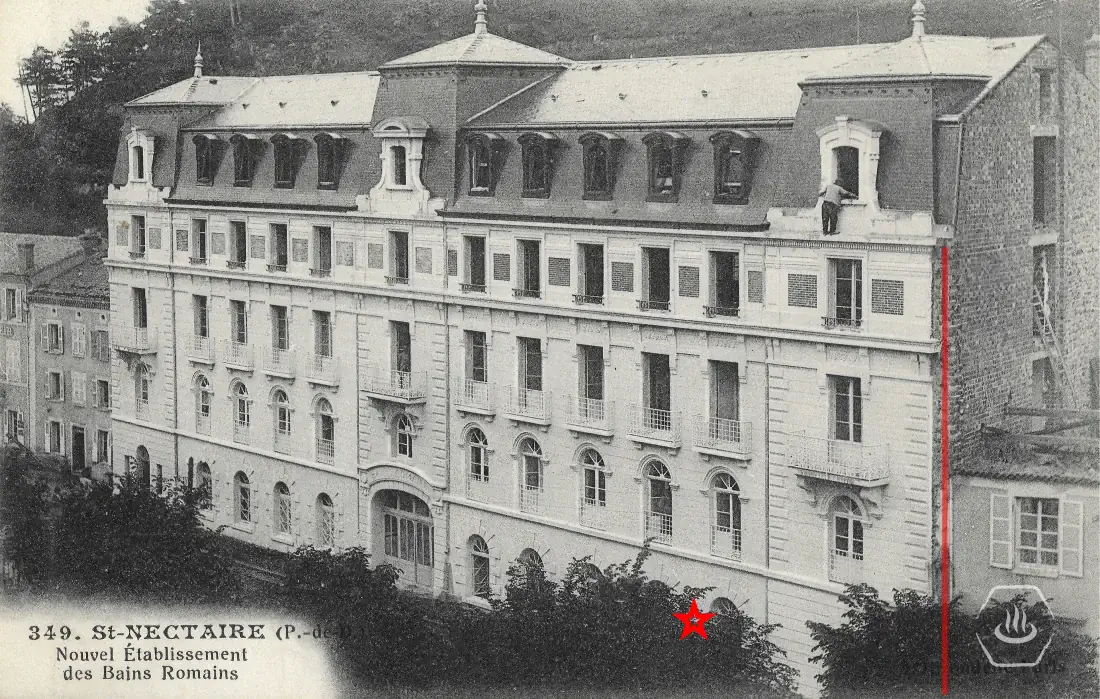

During the 19th century, Les Bains Romains (the Roman Baths) changed hands several times. In 1907, they were purchased by the Société Thermale (which had also bought the other thermal baths), after which they became the Mercure Hotel. The image below shows the extension added to a building originally constructed before the Second Empire. The thermal establishments were expanded and modernised whenever possible.

A building (to the right of the red line on the postcard above) adjoins the west side of the thermal monument known as the ‘Nouvel Établissement des Bains Romains‘ (New Roman Baths), which remains unchanged to this day. This building has one or two storeys and is attached to the monument. It provides access to the thermal monument and the hotel rooms. Together, they form the Mercure hotel.

I discovered this spring while walking down the hotel corridor: it is enclosed on all sides in a small space.

However, this precaution ensures that hotel guests are not disturbed by the smell of rotten eggs. In nature, the presence of this gas (hydrogen sulphide) is identified by its distinctive odour. The fountain is lit from below to accentuate the effect of the water gushing out. However, the source is (normally) located in the basement of the hotel.

The spring owes its name (source Gros-Bouillon) to a spectacular bubbling caused by its high carbon dioxide content, which was once admired by visitors.

♨️ The hot springs of Les Bains Romains:

Source Gros-Bouillon:

In 1840, it supplied over 60 litres per minute at a temperature of 37.5°C. At that time, its waters were channelled with those of the Vieille Source spring on the first floor of the Roman Baths. The Fontaine de la Vieille-Voûte (26.5°C), also known as the Source de la Coquille, was located on the ground floor.

Thus, the Gros-Bouillon spring as it is today is relatively recent, being the result of works carried out on the catchment area throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. This raises the question of whether the current spring has the same physical properties as the ancient spring.

Additionally, its temperature and flow rate decreased somewhat during the 20th century.

In 1920, it was noted that the flow rate had dropped significantly. The flow rate was 40 litres per minute at a temperature of 34°C. At this temperature, taking a bath in running water would not have been pleasant. Some patients therefore felt the need to warm up their baths. Therefore, the water had to be heated artificially.

At the end of the article, you will find the fascinating correspondence of a spa guest who visited the Saint-Nectaire thermal baths in 1914. They were prescribed a bath in running water at 36°C.

Source Nouvelle :

In 1922, drilling was carried out in an attempt to increase the flow of the Gros-Bouillon spring, but it had virtually no effect. However, this resulted in the discovery of another spring, the Source Nouvelle (New spring), which had a flow rate of 60 litres per minute.

In 1928, authorisation to exploit the New spring was refused due to the presence of coliform bacteria in the water. Despite repairs to the hotel’s sewer system, the water quality of the spring did not improve. Nevertheless, it continued to be used for several years. Following yet another attempt to recapture the Gros-Bouillon spring in 1958 — there have been more than a dozen — the New Spring was abandoned.

A ferruginous spring (unnamed)

The spring provides lukewarm (24°C), mineral-rich water that is not sparkling. Bubbling up naturally from the granite rock, the water leaves behind pretty coloured iron deposits. Drinking the water directly from the spring ensures that all of its health-giving properties are retained.

Although its flow rate is higher than that of the Morange Spring, nothing is known about how it was used in the past.

This is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful ferruginous springs in Saint-Nectaire. Yet it remains relatively unknown, even among the locals. There is no information about its history, and the current owner does not know its name.

It is the only spring not to appear on the map because it is located on private property.

As with most springs, these waters deposit carbonates, forming travertine deposits that can be seen around them.

But when you look at the bottom of the catch basin, which is covered in coloured carbonate deposits, you realise just how quickly this phenomenon occurs. The owner cleans it every week. But when the water was drained into an underground pipe, it caused more problems, such as limescale build-up, unpleasant odours and biofilms developing.

Springs and villas

During the thermalism period, it was common knowledge in Saint-Nectaire that many of the villas belonged to spa doctors. As they needed suitable premises in which to practise, most of them rented or purchased villas of various sizes, or had them built depending on their circumstances.

All of the villas mentioned here are located in Saint-Nectaire-le-Bas, close to the former Grands Thermes establishment. They all contain or have access to springs. Most were built around 1890, when the Grands Thermes were constructed.

As its name suggests, this villa was formerly owned by Dr Porge. It is located to the right of the abandoned garden (see the Bélonie Springs).

The location of this beautiful stone house, built practically opposite the Grands Thermes, is certainly no coincidence. According to the current owner, who purchased the property a few years ago, the house is built over two springs, which have since been filled in. A lion’s head on the wall is all that remains, but it leaves a lasting impression.

This beautiful pavilion, where Dr Porge held consultations, housed a ferruginous fountain. Visitors, whether poor, wealthy or unwell, could not use the water without his permission. Those who came to the spring for treatment used the water for medicinal purposes. It was used for oral consumption or to treat eye conditions (as eye drops).

At the time, the most beautiful villa was the ‘Villa Russe’, also known as the ‘Russian Villa’. Its architecture offers a glimpse into the lifestyle of its former inhabitants. Built in 1890 for Prince Orloff, a member of the imperial family, the villa was frequently occupied by him and other family members when they visited Saint-Nectaire.

This impressive residence was once bordered by the Parc de la Source des Dames (Ladies’ Spring), a small princely park. Although the park itself no longer exists, the intermittent spring can still be seen to the right of the villa.

Hidden behind a hedge and fence is the abandoned Ladies’ Spring. Despite its low flow rate, this spring has the highest concentration of arsenic of any in Saint-Nectaire. The old thermal baths are located right next door and now house the tourist office.

There is also a mineral spring inside the villa. The owner experiences some inconvenience due to the limestone deposits it produces.

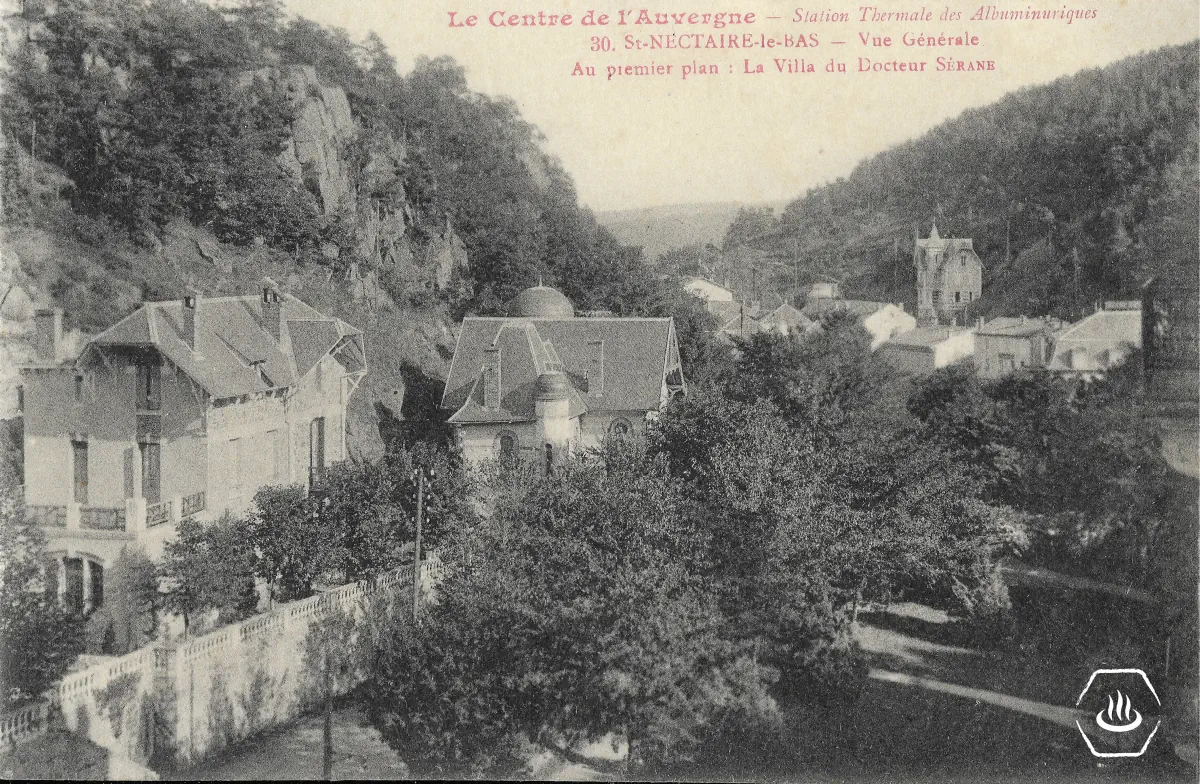

Dr Sérane’s villa, built around 1890, is to the left of the Russian villa.

As its name suggests, this picturesque villa belonged to a doctor from Saint-Nectaire who, like the others, was authorised to prescribe mineral baths for visitors. As was the case elsewhere, visitors needed to obtain a bath number and time slot.

Finally, ferruginous water flows out of two points. This water, which is around 15 degrees Celsius, is connected to the source via a stone conduit. The source can be found in either the villa or the garden.

Built around 1890, the Villa of the Dolmen is located to the left of the Villa of Doctor Sérane. It belonged to Dr Roux, a prominent 20^(th)-century doctor. He was also mayor of Saint-Nectaire for 20 years, from 1945 to 1965. The avenue connecting the two parts of the town is named after him.

The Dolmen spring was developed around 1895 and visitors can access the refreshment area via a wrought-iron gate. It is now abandoned. Of all the springs in Saint-Nectaire, this one has the highest iron content and the lowest mineral content. Behind a stone wall, a cavity collects blood-coloured mineral water due to the presence of iron oxide.

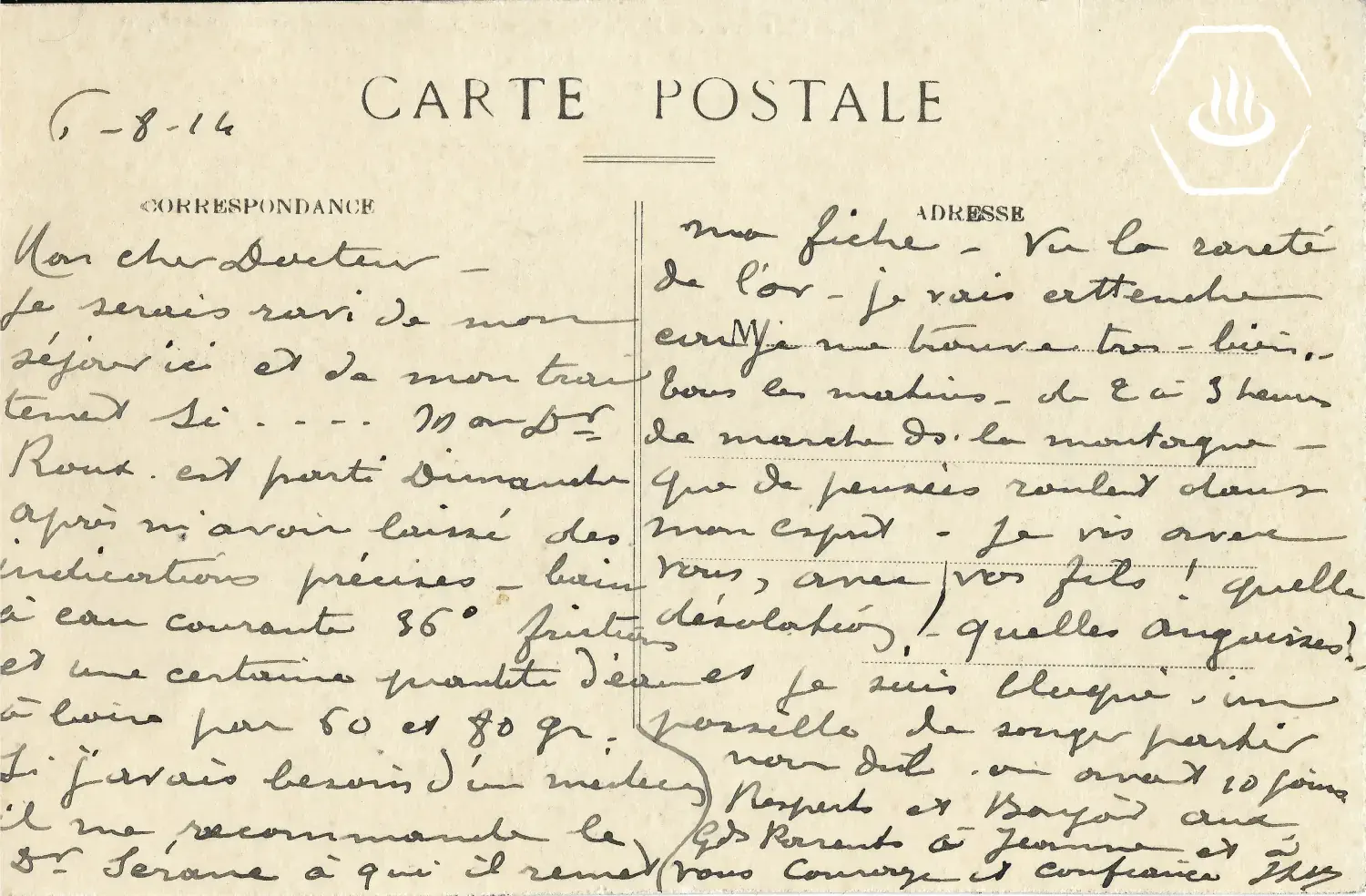

Dear Doctor,

I would have been delighted with my stay here and my treatment if .. Dr Roux had left me precise instructions on bathing in running water at 36°C, applying friction, and drinking a certain quantity of water in portions of 50–80g.

He recommended Dr Sérane (his neighbour) to me in case I needed a doctor and gave him my file. However, given the scarcity of water, I am going to wait a little longer. I am feeling very well. Every morning, I go for a two- to three-hour walk in the mountains. The thoughts that roll through my mind! I live with you and your sons! What desolation! What anguish! I’m stuck here; I can’t think of leaving.